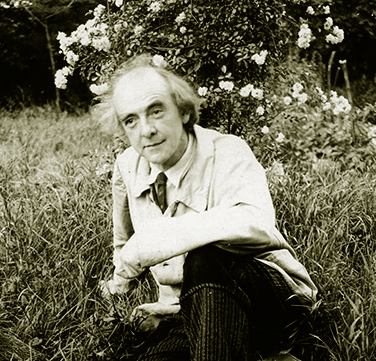

MATTHIJS VERMEULEN

Componist, schrijver en denker

Matthijs Vermeulen (1888 - 1967)

After primary school Matthijs Vermeulen (born as Matheas Christianus Franciscus van der Meulen) initially wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father, who was a blacksmith. Helmond, Vermeulen' birth-place, was at that time a small town with upcoming industry on the edge of the impoverished region De Peel. His parents, who were both of humble origin, had opened a smithy-cum-hardware shop. Matthijs, the eldest son, actively helped with the work in the smithy and after primary school he was to follow in his father's footsteps. However, when he was recovering from a serious illness, his predilection for spiritual matters prevailed and he expressed his desire to become a priest. He went to the seminary of the order of the Norbertines, domiciled in the abbey of Berne in Heeswijk. Here, from one moment to the next - he was then fourteen years old - he became completely obsessed with music, which had not played a significant role in his life until then. He took lessons from L.A. Dobbelsteen, a priest whose church music was inspired by Renaissance polyphony. The lessons were based on sixteenth-century counterpoint (especially that of Palestrina), which was of great importance for Vermeulen's training.

When after two years the lessons came to an end, Vermeulen got himself transferred to the school of his younger brother Christian, a French-speaking Jesuit boarding school in the Belgian town of Thieu, where youngsters of various nationalities were trained to become missionaries. However, the management soon realised that the seminarist did not have a real vocation. After one year, in which Vermeulen received a thorough tuition in classical literature and learnt to speak French fluently, he was asked not to return. Vermeulen never finished grammar school. From May 1906 he stayed at home to prepare himself for a career as an artist.

At the age of nineteen he moved to Amsterdam, where he showed his compositional experiments to the director of the conservatory, Daniël de Lange. He recognised Vermeulen's talent and decided to give him free tuition. As Vermeulen was poor and could not afford tickets for concerts, the only live orchestral sound he heard, was that of the fragments of music that could be made out at the gates of the former garden of the Concertgebouw. He spent a lot of time studying in his room, or in the university library.

Music critic in Amsterdam

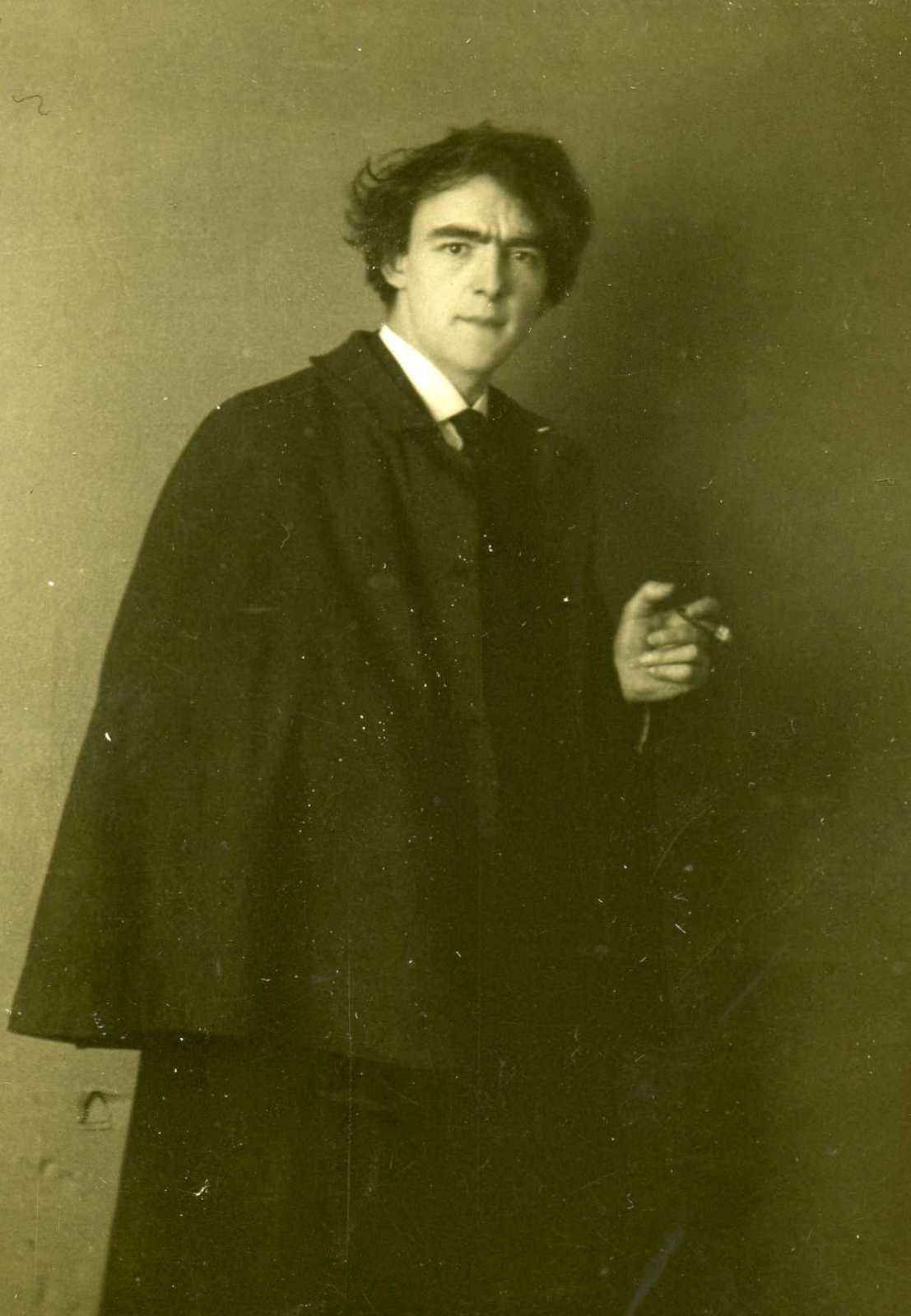

Vermeulen started his public life as a writer. In 1909 he became a critic on the Catholic paper De Tijd and within a remarkably short time he developed an independent voice. On recommendation of Alphons Diepenbrock he was offered a position at the weekly paper De Amsterdammer (De Groene) in October 1910. As Vermeulen was also appointed a correspondent on the NRC, that season he wrote for three papers.

The acquaintance with Diepenbrock was the beginning of a long relationship. The composer, who was 26 years older than Vermeulen, became his tutor. He lent him books and scores, criticised his articles and gave advise and suggested sources for his polemics. Diepenbrock's influence is especially noticeable in Vermeulen's treatment of the antithesis between the 'Teutonic' and the 'Latin' spirit in art. During these 'lessons' Diepenbrock illustrated his views with music examples which he played on his Erard.

In a short time Vermeulen became an authority. As an advocate of the new French music, he came into conflict with Willem Mengelberg whom he highly respected as a conductor but who, in his opinion, failed as the musical leader of the most important music organisation of the Netherlands, the NV Het Concertgebouw, because of his one-sided focus on German music. Not everybody was happy with Vermeulen's criticism and eventually it gave him the reputation of being Mengelberg's opponent. No doubt Vermeulen's experience with the music that was played in the Concertgebouw in those years (premieres of Mahler's Eighth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde, inspired performances of Debussy, Bruckner, Diepenbrock, Strauss, Schönberg, Musorgsky and Skryabin) contributed to the rich orchestration of his First Symphony, the sunny and youthful Symphonia Carminum, which he composed between the summer of 1912 and 1914.

After the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Vermeulen went to the editorial office of De Tijd and offered his services to report from the front as a war correspondent. He gave detailed descriptions of the devastation in Belgium and the north of France. Seeing the useless, systematic destruction of human lives and culture confirmed the anti-German sentiments that had been aroused in conversations with Diepenbrock. Back in Amsterdam echoes of this aversion frequently found their way into Vermeulen's reviews: for him culture and politics could not be separated. In 1915 he moved from De Tijd and De Groene to the, in those days, progressive and anti-German paper De Telegraaf, where he became head of the 'Art and Literature' department.

In October 1915 Vermeulen sent his First Symphony to Mengelberg, who kept him in suspense for a year and then rejected the work with the denigrating advise that he should take lessons from Cornelis Dopper. Due to the conductor's powerful position, Mengelberg's verdict meant a veto for Amsterdam.

In 1917 Vermeulen composed four songs, all inspired - though in different ways - by the war: On ne passe pas for tenor and piano (Victor Le Jeune), Les filles du roi d'Espagne for mezzo-soprano and piano (Paul Fort), The Soldier for baritone and piano (Rupert Brooke) and La veille for mezzo-soprano and piano (François Porché). 'Victor Le Jeune, soldat au front' was the pseudonym of Elisabeth Diepenbrock-de Jong van Beek en Donk, Diepenbrock's wife with whom Vermeulen had a passionate affair for a year.

In December 1917 Vermeulen met his future wife, Anny van Hengst. They got married on 21 March 1918. The following May Vermeulen started his First Cello Sonata, which he completed four months later. At the same time he compiled two collections of articles, entitled De Twee Muzieken (The Two Types of Music) for a series on French art.

Bottled up annoyance about the fact that there was no substantial change in the programming made Vermeulen cry out 'Long live Sousa' in the concert hall after the performance of Dopper's Zuiderzeesymfonie (Zuyder Zee Symphony) - the second within a year - on 24 November 1918. This outcry caused a tremendous uproar. People thought Vermeulen had shouted 'Long live Troelstra'. To the average concert-goer this was a scary provocation: only a week before socialist Pieter Jelles Troelstra had announced the revolution of the proletariat in Parliament. The board of the Concertgebouw ordered Vermeulen to leave the concert hall and temporarily denied him access. After this riot there were several rowdy concerts. At one of them supporters of Vermeulen's views were roughly removed. Through the pressure of public opinion the critic was readmitted.

Vermeulen's opponents also drew his First Symphony into the long-lasting polemic about this incident. They insinuated that Mengelberg had declined from performing the work in order to save the inexperienced composer from loosing face. Vermeulen felt compelled to get the work performed, so the audience and critics could form their own judgement. On 12 March 1919 the 'symphony of the critic' was premiered by Richard Heuckeroth, the conductor of the Arnhem Orchestral Society. It was a disastrous performance: the cast that was decimated by the Spanish flu, played from uncorrected parts. Nevertheless, the piece held. Some reviews were even altogether positive. However, the composer did not want to attend the repeat in Nijmegen.

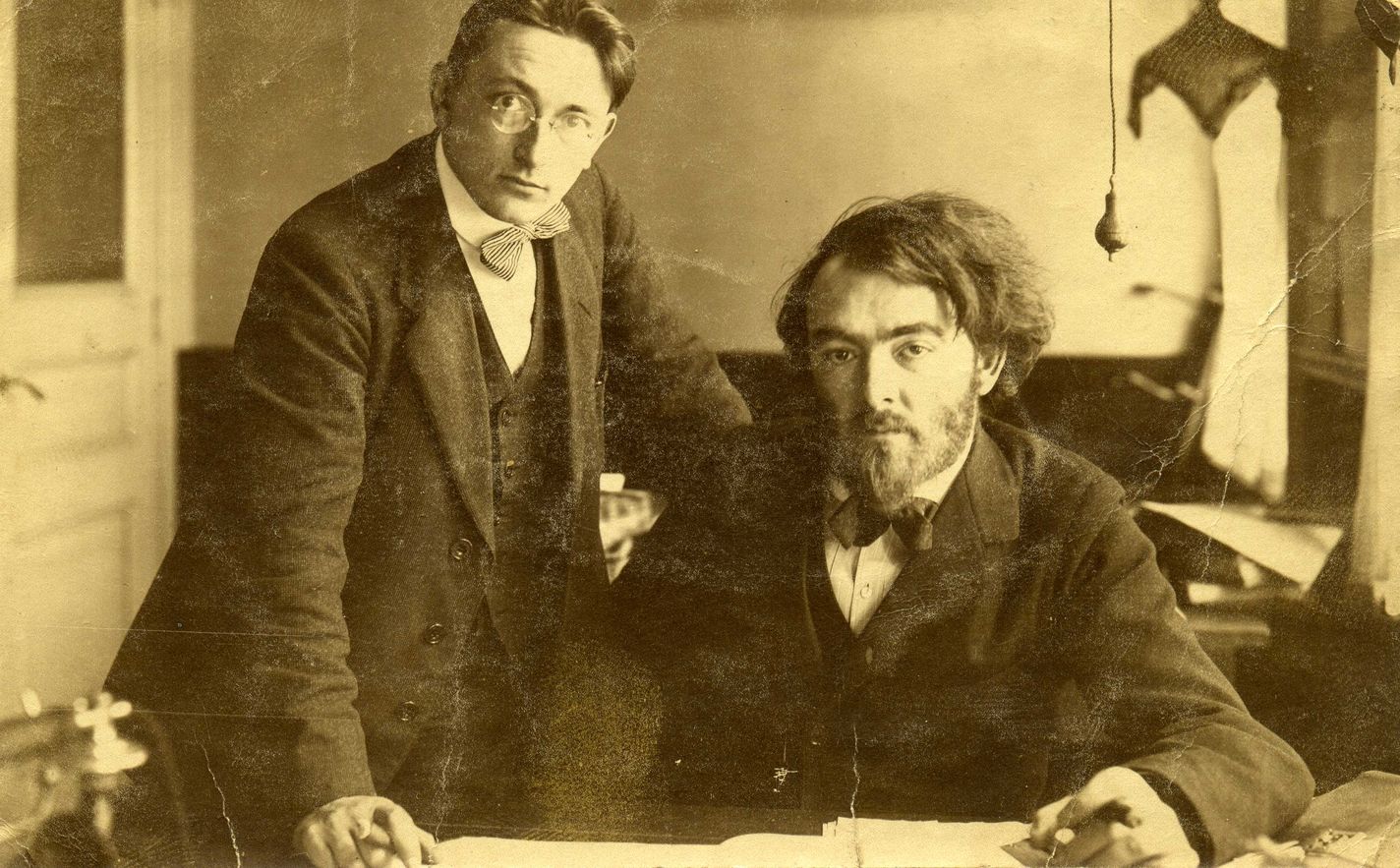

After starting his Second Symphony, Prélude à la nouvelle journée, in 1919 Vermeulen started to find his work as a critic harder and harder. In the summer of 1920 he resigned so he could devote himself entirely to this revolutionary work. Friends organised financial support for two years and offered him the use of a house in Hollandsche Rading. Here he completed his Second Symphony in 1920. At the end of March 1921 he started the next. During that period Vermeulen had a lot of contact with Willem Pijper.

To France

In April 1921 Vermeulen made a last attempt in writing to interest Mengelberg in his work. Mengelberg, however, remained silent. Vermeulen proceeded to publish his letters under the title Bijdragen tot de Muziekgeschiedenis van dezen tijd (Contributions to Contemporary Music History) in De Nieuwe Kroniek, 7 May 1921. Then he decided to emigrate to France, where he expected to find an amiable climate and kindred spirits. In July 1921 Vermeulen and his wife and two children moved to La Celle-St.Cloud, a village south-west of Paris, where he concluded his Third Symphony, Thrène et Péan on 9 September 1922.

At first everything appeared to be going well. Vermeulen got in touch with key figures in the French music scene, including Gabriel Pierné and Darius Milhaud. The conductor Pierné was interested in Vermeulen's First and Second Symphony. However, he thought the technical demands and the large orchestra presented insurmountable obstacles, as a long rehearsal time and extra musicians would be required: for French orchestras that depended on receipts, they were too great a risk. In 1923 two songs and the First Cello Sonata were accepted by the jury of the chamber music society, Société Musicale Indépendante. Ernst Lévy, the pianist who had performed the cello sonata at the premiere in Paris on 6 June, became a good friend of the composer. Vermeulen's work was also appreciated by Nadia Boulanger, an important figure in the Paris music scene. To thank her for her support, he dedicated his String Trio, composed in 1923, to her. She introduced him to Serge Koussevitsky, who was enthusiastic about the Third Symphony. He made plans to perform the work in America with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. For this purpose he had the parts written out. However, when he got to know the musical climate in America better, he changed his mind.

After various attempts to get his symphonic work performed had failed, Vermeulen realised that the breakthrough he had hoped for, was an illusion. He did not feel like going ahead with a new symphony without having put the experiments in the previous symphonies to the test. For a while he only wrote chamber music, for which he believed there were still opportunities. This resulted in the Violin Sonata (November 1924 - April 1925). Vermeulen got some satisfaction when the Cello Sonata was published by Senart in 1927. In that year he started composing a second sonata for piano and cello.

Correspondent of a newspaper in the Dutch East-Indies (Soerabaiasch Handelsblad)

Slowly but surely the financial situation of Vermeulen's family (by then there were four children) became impossible. When in 1926 the opportunity arose to earn a living as a correspondent in Paris on a newspaper from the Dutch East Indies, the Soerabaiasch Handelsblad, he seized it immediately. From August 1926 to May 1940 Vermeulen every week produced two 'Parisian Letters' on a wide variety of topics: national and international politics, economy and finance, theatre, literature, painting, technology and science, history, new types of automobiles, aeroplanes and submarines, sports, crime and faits divers (even fashion!). Only on rare occasions did he write an article about music. The long and often virtuoso articles were read eagerly by the cosmopolitan society in the port of Surabaya. They required so much of the author's attention and energy, that he stopped working on his Second Cello Sonata.

At the end of 1929 Martinus Nijhoff requested him to compose music for the festive play De Vliegende Hollander (The Flying Dutchman), which was to be performed on the lakes near Leiden, the Kager Plassen, for the 355th anniversary of the University of Leiden the following summer. To address the audience new techniques were used: Vermeulen's symphonic music, recorded in a Parisian studio, was played back through electronic amplifiers. However, during the performance the weather conditions were unfavourable. A strong wind blew the sound away, so the press and audience noticed little of Vermeulen's contribution to the production. For a long time Vermeulen did not compose. It was not until 1937 that he took up the Second Cello Sonata.

Back to music

The desire to write for orchestra again was kindled in May 1939, when Vermeulen attended the premiere of his Third Symphony in Amsterdam at a concert given by the committee Manifestatie Nederlandse Toonkunst (Manifestation of Dutch Music). The performance by Eduard van Beinum and the Concertgebouw Orchestra confirmed Vermeulen in his conviction that his compositional ideas were right. When a year later it became impossible to continue his journalistic work because all connections with the Soerabaiasch Handelsblad were cut off due to the German invasion of the Netherlands, Vermeulen once more dedicated himself entirely to music. On 1 July 1940, just after his return from the so-called 'Exode' (the mass flight of the Parisians from the German army), Vermeulen put the first notes of his Fourth Symphony on paper. Firmly believing that the war would end well, he called it Les victoires.

For four years Vermeulen composed non-stop. After completing the Fourth Symphony in June 1941, he made three arrangements of the Ave Maria, the Trois Salutions à Notre Dame for voice and piano, on request of his children. Next, in October 1941, he started his largest work, the Fifth Symphony, which he put the finishing touches to in January 1944. Then the poem Le balcon by Charles Baudelaire inspired him to write a song for mezzo-soprano or tenor and piano. After that the tension of the times (the Allied landing on 6 June) brought his inspiration to a halt and he started a revision of the Fifth Symphony, which he called Les lendemains chantants, after the words of a fusilladed leader of the French communist party, Gabriel Péri.

Shortly after the liberation of Paris Vermeulen suffered some terrible blows. In the autumn of 1944 he lost both his wife and his favourite son Josquin. His wife, who was much weakened because of the food shortage, did not survive an operation. His son fell in the Vosges when his unit of the French liberation army was surrounded by the Germans. Vermeulen's mourning process took shape in a moving diary which he later titled Het enige hart (The Only Heart). In his notes he carried on the exchange of ideas with his deceased wife, sometimes sensing signs of her presence, at other times despairing the severance of the contact. Vermeulen's search for the meaning of his losses gradually resulted in a comprehensive philosophical work, which he developed in his book Het Avontuur van den Geest. De plaats van den mens in dat avontuur (The Adventure of the Spirit. The Place of Man in that Adventure). The publication not only aims to be a declaration of faith based on logical reasoning, but also an appeal to use the knowledge of the atom purely for the good. (Deeply shocked by the destructive effects of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Vermeulen found mankind confronted with an awesome turning-point in history: the option of the total destruction of life.)

A new life in Holland

In 1946 Vermeulen married Thea Diepenbrock, the daughter of his former tutor. He moved to Amsterdam, leaving behind most of his books and possessions, and returned to the Dutch music scene as a critic on the paper De Groene Amsterdammer. He not only published articles in which he reported lyrically on the achievements of the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Eduard van Beinum and in which he spoke enthusiastically about satisfying developments in Dutch composing (he praised the works by Rudolf Escher), but he also published sharp, polemic articles. One of the things that enraged Vermeulen was the performance of Richard Strauss' Metamorphosen, which he - wrongly - considered an In memoriam for Hitler. He received the Meulenhoff Prize for his book Princiepen der Europese muziek (The Principles of European Music) in 1948.

The following year promising developments took place with regard to Vermeulen's compositions. In September 1949 Eduard Flipse performed the Fourth Symphony with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and less than two weeks later van Beinum played the Fifth with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. However, these were one-off events. Van Beinum was opposed by his board and Vermeulen had such a heated disagreement with Flipse (about cuts in one of Diepenbrock's works), that he felt obliged to ask the conductor to return the scores he still had at home. In 1953 Vermeulen was awarded fifth prize at the Reine Elisabeth Competition in Brussels for his Second Symphony, which still had not been performed. However, it took a long time before a Dutch orchestra put the winning work on its programme. In the first half of the 1950s only the Passacaille et Cortège from the music for De Vliegende Hollander was performed several times.

The stifling atmosphere of the cold war, in which politicians and military leaders appeared to be steering toward a nuclear confrontation, had a depressing effect on Vermeulen. Several times he took a stand in De Groene Amsterdammer against developments such as the continuing increase of the budget for arms of the NATO countries and strategists' open plea for a radio active curtain between the West and the East. In order to spread his arguments against negativism more widely, Vermeulen published an exhaustively updated French translation of Het Avontuur van den Geest, financed mainly by himself. He also wrote articles for the communist paper De Waarheid (The Truth) and for Vrede (Peace), the organ of the Nederlandse Vredesraad (Dutch Peace Council). In 1955 this organisation invited Vermeulen to give a speech to close the first demonstration against the atom bomb in the Netherlands. In his fiery address entitled 'Nuclear Weapons and Our Conscience' he said: "The atom bomb is a weapon that is anti-Life, anti-God, anti-Mankind."

As part of the Holland Festival 1956, Eduard van Beinum and the Concertgebouw Orchestra gave the Dutch premiere of Vermeulen's Second Symphony. Once more the performance of a symphony was the incentive for a new period of composing: "I regained the desire and the courage to start a new life." After ten years of writing he finally decided to quit journalism and dedicate the rest of his life (at the age of sixty-eight he felt that he had been in 'the last quarter' for some time) exclusively to composing. He left the city and settled in Laren with his family.

The last compositions

In two years (November 1956 - November 1958) he wrote a new symphony, the Sixth, which he called Les minutes heureuses, after the line "Je sais l’art d’évoquer les minutes heureuses" by Baudelaire, which he had set to music before in Le balcon. The sudden death of van Beinum (who had programmed the work) in April 1959 was a great loss to Vermeulen. Paul Hupperts and the Utrecht City Orchestra took over and performed the Sixth Symphony on 25 November 1959.

Earlier that year Vermeulen had composed the large-scale song Prélude des origines for baritone and piano on a text by Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. He was commissioned by the government to write a song cycle, but put it aside to work on his Sting Quartet (December 1960 - June 1961), for which he also received a grant from the Ministry of Cultural Affairs. In September 1962 Vermeulen completed his Trois chants d’amour for mezzo-soprano or tenor and piano.

Although Vermeulen did not see many hopeful developments in the world (he often had great inner conflicts between optimism and pessimism), he wished to keep faith in a better future for mankind. The tone and title of his last work, the Seventh Symphony Dithyrambes pour les temps à venir (Songs of Joy for the Times to Come), composed between March 1963 and June 1965, bear witness to this positive tendency. The performance of the First Symphony by the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Bernard Haitink in 1964, fifty years after its completion, counted as the real (and this time a very satisfactory) premiere of the early work in which he had already applied his ideas about joining independent melodies.

Soon after the Seventh Symphony was completed the first signs of an incurable form of cancer in the head manifested themselves, gradually affecting his hearing. This prevented him from attending the premiere that took place on 2 April 1967 (also by the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Haitink). A few months earlier he still had the energy to produce a very impressive article in which he warned against the danger that he believed lay in the so-called Notenkrakers' actions against the Concertgebouw Orchestra: "One does not put one of the most beautiful human inventions, the symphony orchestra, at such risk."

The composer died after a long period of sickness (his wife and daughter nursed him at home) on 26 July 1967.

(Translation: Hilary Staples)