MATTHIJS VERMEULEN

Componist, schrijver en denker

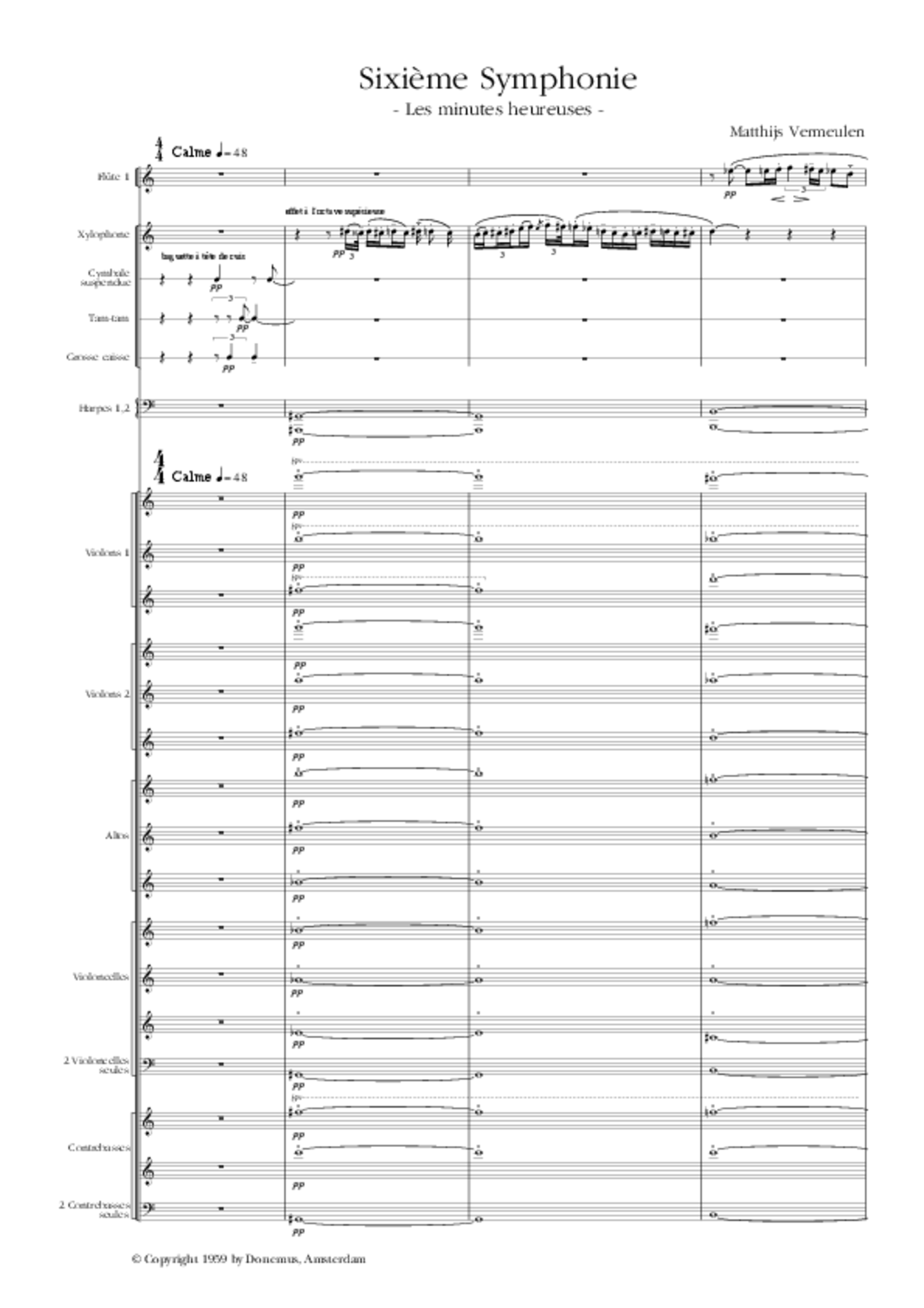

Sixth Symphony LES MINUTES HEUREUSES (1956-58)

Notes on My Sixth Symphony

published in Delta. A Review in Arts Life and Thought in the Netherlands (Autumn 1961)

The leading idea for a composition is always suggested to me by the subject, the action; and the theme for my Sixth Symphony came to me as follows. One evening my wife and I were talking about music of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. After a while our conversation turned to a composer from southern Brabant who was quite famous in his day but has now long since been forgotten. He was called Matthijs Pipelare,Matthew – the Piper - a rather curious name that Alphons Diepenbrock once in a jovial mood had transferred to me, because my musical technique in some ways resembles that of the Renaissance composers. Pipelare used to write the first half of his surname in letters and the second half, la re, in notes. La and re are the two principal tones of the Dorian mode.

In the course of our conversation one of us brought up the tonal formula la do re, and since we are both incorrigible francophiles, we heard the three syllables not only as notes but also in their metaphorical, allegorical sense as the French word l'adoré, the adored, the adored one. We smiled. At this my wife, who knows my leanings towards admiration and adoration, suggested that I should compose a piece of music on the notes. I thought for a moment and then said I hadn't the time. I recalled the romantic story recorded in the memoirs of Berlioz, who had an inspiration for a wonderful symphonic theme one night and noted it down, only to tear it up the next morning and forget it, because he would otherwise not have been able to write the weekly article with which he earned his living. At that time I was still working on my book Het avontuur van den geest (The Adventure of the Spirit) and had to write my weekly article for De Groene Amsterdammer. All my life I have been unable to combine the two conflicting mental activities, the one synthetic, the other analytic, of composing and criticism.

That was any number of years ago. By no means easy years. Yet during those thousands of days of practising patience, I now and then recalled that evening and its three notes. I calmly refused their invitation. There was not much chance of my ever forgetting them: they were so simple, so lapidary, so laconic. Moreover, they had apparently taken root in my subconscious, and we never know precisely what happens there. They lingered on, lying dormant, without suggesting any future for themselves. Then, one day late in June, while I was in the train to The Hague on my way to a festival concert, I suddenly saw in the evening sunlight a wonderfully pink piglet scampering all by itself through the fields with the exuberance of a winged creature, and I felt as if a curtain had been raised within me which until then had separated me from a certain sound. I heard something that sounded like an opening; I heard the beginning of a subject that engraved itself on my memory. Strangely enough I thought a moment later of a Pythagorean basilica which railway constructors had recently uncovered near Rome, a temple where young pigs had been sacrificed to the gods.

When some time later I was freed from my obligations as a critic, I had a subject, adoration, but no leading idea. I was confronted with the problem how such a vague yet age-old, ultra-human, and universal idea as adoration could be transformed into a musical composition which would from the very beginning develop lucidly and gradually to its logical conclusion. For in a composition one cannot fall in somewhere in the middle, nor can one stop halfway. The composer must pursue his idea to its extreme if he does not wish to leave the listener with a feeling of dissatisfaction. With the finale before me as an idea, a working hypothesis, an ideal, and sometimes even as an experience, I sought for the juncture where one extreme would meet the other.

I did not find it at once, but it was there for the asking. It was at the beginning, of course, at that moment when there is virtually nothing stirring that betrays emotion. For me adoration is synonymous with emotion. Although emotion is possible without adoration, and adoration without emotion, for me they are inseparable. I have something of the sacramental in me, perhaps more than a Babylonian or Egyptian of six or seven thousand years ago might have had; and like him, only rather more rationally, I see all things animate and inanimate in the light of their adorable, fascinatingly beautiful mystery, for all things are masterpieces. Accordingly I envisaged the beginning of that still almost imperceptible emotion as friendly, affectionate, more or less enamoured, gentle, and already capable of arousing sympathy. It would make its appearance in the guise of a clearly rounded melody. What this melody would express could not be defined in words. It would well straight up from the spring where emotion is still pure energy, where, still unnamed, it is the sheer expression of a newly awakened delight.

When this melody was finished it would be followed by another one, closely related in spirit and therefore completely natural, somewhat more explicit and a trifle more intense. And after that would come, either with or without the intervention of short, fleeting intermezzos, a third, a fourth, a fifth melody, each arising at a slightly higher level of life, pulsation, and warmth, and continually from the same source of unnamable but ever gratifying motion which would manifest itself in ever new melodic lines, each a little more vibrant and livelier than the last, the one somewhat shorter, the other somewhat longer, all different in character and temperament and yet fundamentally the same, all instantly recognizable and familiar, but not to be captured in a word or confined to a space. The upward trend should be unlaboured, and without hiatus or interruption. There might be breathing spaces in the action, but no breaks. The tempo, rhythm, and accents should harmonize with the gradual increase in motion. All the melodic lines would have to be more or less directly connected with the three tones la do re which had accompanied me unproductively for ten years, yet these tones would be allowed to dominate the action in only a few exceptional places and would otherwise serve merely as a centre for construction.

I did not know, when I began, how many melodic lines I should need to bring this musical action to a logical conclusion. I did not count the number of what I myself thought of as panels Ot scenes, although they were beyond the visible even to me. I knew only that I would go, and would have to go, to the furthest extent of my powers, and that the entire action would take place on this earth. Hence the symphony is constructed along the simplest possible lines. Graphically it might be symbolized by a spiral or a crescendo mark. The music nowhere returns to a bygone point. We never bathe twice in the same stream, as Heraclitus said.

Such is the leading idea behind my Sixth Symphony. In outline it might be said to represent the perpetual growth of life in its many stages and phases, or rather of the spirit that gives life its animation. Its composition entailed many risks, and at every upward step there was the danger of foundering. But the idea was imposed upon me by the subject and was inescapable. The structure that resulted from it is, to my knowledge, unlike anything in the history of music; neither does it occur in any of my previous symphonies. The only possible parallels I can think of are Dante's Divine Comedy with its ever rising circles and perhaps Hieronymus Bosch's phantasmagoric painting in the Escorial, which we in the Netherlands call The Garden of Pleasure, but to which the French have given the more imaginative and subtle name of La poursuite des délices terrestres, the pursuit of terrestrial delights. With this distinction, however: the scenes of the Sixth Symphony have no concrete, extramusical connotations.

The technical means with which I accomplished the composition are the result of a number of propositions aiming at a reform in the composer's material. These propositions have not yet been discussed. But I think that an enumeration of them and a brief elucidation should make it easier to listen to a kind of music seldom heard. There are two ways of listening to music, the one intuitive (and this can indeed be adequate), the other intellectual (which is bound to be more complete), and it is characteristic of the intellect that it wishes to understand, particularly when it is overwhelmed.

I have always endeavoured to do away with the rhythm that divides time into small units of two or three beats (or a multiple of two or three) with the accent invariably on the first. I have always tried to make time more relative, more intangible, more indefinite, not immediately recognizable and limited by the readiness with which it allows itself to be measured. I have always attempted to expand and enlarge time into two, three, four, or five different simultaneous times which woven together form unrestricted, limitless time, in the same way that various times go to make up tinie in the vast space of the universe.

Ever since Wagner first used five-quarter time in his Tristan, composers have been tampering with our metrical system in an effort to escape from the confinement of the bar-line, which over the past five hundred years has disrupted the flow of music like the ticking of an old-fashioned pendulum-clock. Such an escape cannot be effected by making changes in the metre or complicated differentiations of note values, nor can it by combining two or more independent rhythms. All these expedients inevitably remain variants of the same method of measuring time.

The sensation of free measure, of continuity, of astronomical, cosmic time (in which we have already begun to live and in which we shall live increasingly in future) can be achieved only by the elimination of the solo voice as such and by the consistent individuation of all the secondary voices that accompany the leading voice in symphonic, orchestral music. By individuation I mean that each accompanying voice should sing its own melody, and that this melody should follow its own central rhythm, which ought to be independent of the principal central rhythm. Sonority and expression are the sole permissible links between the leading voice and the secondary voices. It is only in this way that the centre of gravity and the strictures of gravitation entailed by it may be eliminated and the sensation given of freedom in time and space.

This technique may be formulated easily enough in theory, but to put it into practice is more difficult and makes great demands upon the composer. First, he must be able to hear and think in terms of this technique, an accomplishment that can be acquired, though it demands a particular turn of mind. Secondly, he must have at his disposal a fertile imagination and a robust gift for melodic invention. Thirdly, he must have just as great a command of counterpoint as Palestrina and Bach. Finally, he must have a complete grasp of the chordal possibilities of contemporary music.

The application of this technique likewise implies the radical abolition of the entire system of cadence, phrase construction, tonal grouping, and ground bass, both in the relations of the tones of the melody to one another and in the relations of the chords to one another. Debussy introduced such a reform, without being capable of carrying it through to its conclusion, but no attempts have since been made to follow in his footsteps. Nevertheless this reform is of prime importance, presenting as it does the only avenue of escape from the vicious circle in which composers have been gyrating almost blindly since about 1920. If we desire a further and fruitful evolution of music, a fresh start will have to be made in musical thinking.

The gamut of this technique is the twelve-tone scale, but then without any restrictions in the sequence of tones, which should be governed only by the chosen tonal centre – something that can be changed at will or according to necessity - and the demands of the melody. Any preconceived constraint in the sequence of the tones as decreed by the dodecaphonists I consider tyrannical dogmatism and a pointless denial of freedom which cannot be justified by any intellectual arguments or even by any pretexts whatsoever. I am convinced that if, around 1750, the first symphonic composers who made use of the ordinary scale had got it into their heads to enact the same unnecessary, unmotivated law, they would have brought the whole evolution of music to a standstill.

The twelve-tone gamut, as I see it, could be called an integral chromatic scale were it not for the fact that the word chromatic arouses wrong associations. For in the traditional chromatic scale sharps and flats are always closely bound up with their natural tones. Yet as I visualize it, each of the twelve tones has completely equal rights and is dependent only upon the previous or following tone in so far as the curve of the melody requires it. Hence it would be more correct to call this an integral diatonic scale, in accordance with the etymological meaning of diatonic: a gamut through which all tones move.

The innovations I have made in the various fields of technique are an organic product of the views I have always held concerning composition as such and the treatment of the orchestra. It is my belief that all the traditional forms handed down to us are outlived and exhausted, and that they are no longer either expedient or fruitful. We may indeed still admire them as more or less perfect examples of a bygone method of musical expression, but they have ceased to answer to the conscious or unconscious desires of our deepest instincts. For us with our less rudimentary, broader, more complex, and deeper knowledge of psychology, the sonata form, the lied, the rondo, and the fugue have lost their significance, their appropriateness, their raison d’être, because we have gradually come to realize that after a series of more or less delightful or distressing experiences in life, whether spiritual or physical, we never return to our exact point of departure as if nothing had happened, in the over-simple way symbolized by the old forms. Indeed, such composers as Berlioz, Liszt, Strauss, and Mahler tried to get round the requirement of a conflict between two contrasting themes, that complex which has curiously paralysed music for a century and a half, either by increasing the thematic material or by giving the complex legitimate status through the addition of a literary scenario. But in spite of themselves they always reverted to the traditional law of repetition, according to which everything started again as if the listener had not heard a thing and was still in the same frame of mind as at the beginning. I have never been able to discover why or how the validity could be proved of one exclusive system which emerged as an obligation at a relatively late stage in the history of music. Ever since my youth I have held that every preconceived, so-called traditional form merely prevents an idea from creating its own form, and that it ought therefore to be resolutely shunned.

Not only have I always thought that the forms used by composers of the past were outmoded, but also that all the standard sorts of subject matter should be avoided, unless it appeared possible to renew them entirely. Such subject matter was always drawn from some social custom such as the hunt, a parade, a procession, a dance, a march, a serenade, an aubade, or from some recognized facet of life such as the church, a temple, a prie-dieu, a cradle, domestic or rustic scenes, and all the picturesque events of day and night. And it was realized with all the symbols of rhythm and sound available as the conventional means of expressing ideas which, to my mind, no longer have any significance in contemporary life.

But even though I realized that there was scarcely anything in the entire range of ideas of former masters, or even in a large part of their musical vocabulary, which I could take as my example and upon which I could build, it was nevertheless quite clear to me that these masters had, each in their turn, accumulated spiritual and emotional resources which would henceforth be considered as a standard, below which I could not permit myself to descend and above which I wished to rise as much as was in my power. All the composers of the past that I admired had listened to and obeyed the selfsame impulse.

Consequently I dreamt of musical forms which differ one from the other just as each new play by a particular playwright differs from the last, each new novel by the same novelist, each piece of sculpture by the same sculptor, each painting by the same painter, and each building designed by the same architect. I dreamt of musical forms which, just as in the other arts, were dictated solely by the subject. Like my predecessors I derived these forms from the impulses alive in society, but on another level of sensibility. Instead of interpreting specific feelings which are bound up with a host of conventions and which I have moreover seen debased by tricksters and charlatans of all ranks and classes into the most venal merchandise, I believed that I should make an attempt to broach the most fundamental principle, and by this I mean that hidden abode where man is not yet himself and yet infinitely more than himself; the spring from which that mysterious urge rises which every man bears in his heart - more or less dormant, mostly unexploited, and often unbeknown - that unfathomable urge to be a poet in the original sense of the word, namely, a maker, a creator; that dully glowing core in each of us, where demiurgic fervour, devoid of all restraint and comparable only with love in its first stage, when it has as yet no object, when it is only the state of loving, is always waiting for an opportunity to burst into flame.

This nameless urge would then be turned into sound in countless situations, in innumerable melodic lines, and each of these situations and lines would always find positive expression. This powerful and beneficial urge would not be personified by a solo voice, representing a corporate body, but by an ever-changing number of individual voices, so arranged that together they form a corporate body in which every voice participates actively and individually in the birth of the music and in its every fluctuation. The composer would no longer contemplate the orchestra from without, as accompanying or illustrating a single, individual voice; he would see it from within as a corporate body of diverse but equal voices striving towards the realization of the song of humanity. With such ideas as these in mind I composed my six symphonies; they all differ in action and content and have been constructed without the support of any traditional form, and their solidity, their diversity, their free naturalness, and their unity and logic have never yet been called into question. I do not think it out of place here to remark that for many years opponents of modern music have continually denied even the mere possibility of establishing a firm, sturdy, acceptable, organic musical structure without the aid of classical forms. I may say that this denial has been reinforced by modern composers, who without exception have shown far too little concern for the logicality, the importance, and the value of structural design, thus preserving and perpetuating the traditional forms.

When I started composing, a good half century ago, I should not have been capable of laying down methodically and lucidly a set of coherent principles upon which my own style was modelled. In our work, particularly when we are young, we are enveloped by the growing idea in which we live as in a glass-case, and we trouble ourselves little, and then only in large, with the theoretical motivation for what we are creating with a certain fervour. And once I had finished a work, to see it remain unperformed for twenty, thirty, or forty years, I never found opportunity either to explain or to defend the premises upon which it rested. The few times that I have tried to open a discussion (for example with Alfredo Casella**) on fundamental questions concerning musical thinking and composing, my attempts have invariably been greeted with nothing but silence.

Gazing back on the task of a lifetime, however, I am encouraged to think that it is possible for me to deduce from the work I have done a number of set principles which have proved their usefulness and applicability in practice, and which have at the same time shown themselves to be desirable, I may say indispensable, for the future. For looking round at all the attempts being made well-nigh everywhere by present-day composers to escape from the impasse into which the great masters of the end of the last century and the beginning of this seem to have brought music, I see as much to my sorrow as to my surprise that if I had still to make my debut as a composer, I should be faced with the solution of precisely the same problems as fifty years ago. The famous avant-garde of those days, Schönberg, Berg, Webern, and Stravinsky, whose work I knew well enough in 1914 to take advantage of their finds and to avoid their shortcomings, are even today in almost every country, including the Netherlands, the examples for a new generation which is trying in vain to make up for a lost past. So, contrary to my intentions, I am for the second time in my life in the paradoxical position of being thirty years in advance of the times. For I am well enough aware of what is lacking in contemporary music to feel an ardent desire to supply the deficiency. And in this I shall persist.