MATTHIJS VERMEULEN

Componist, schrijver en denker

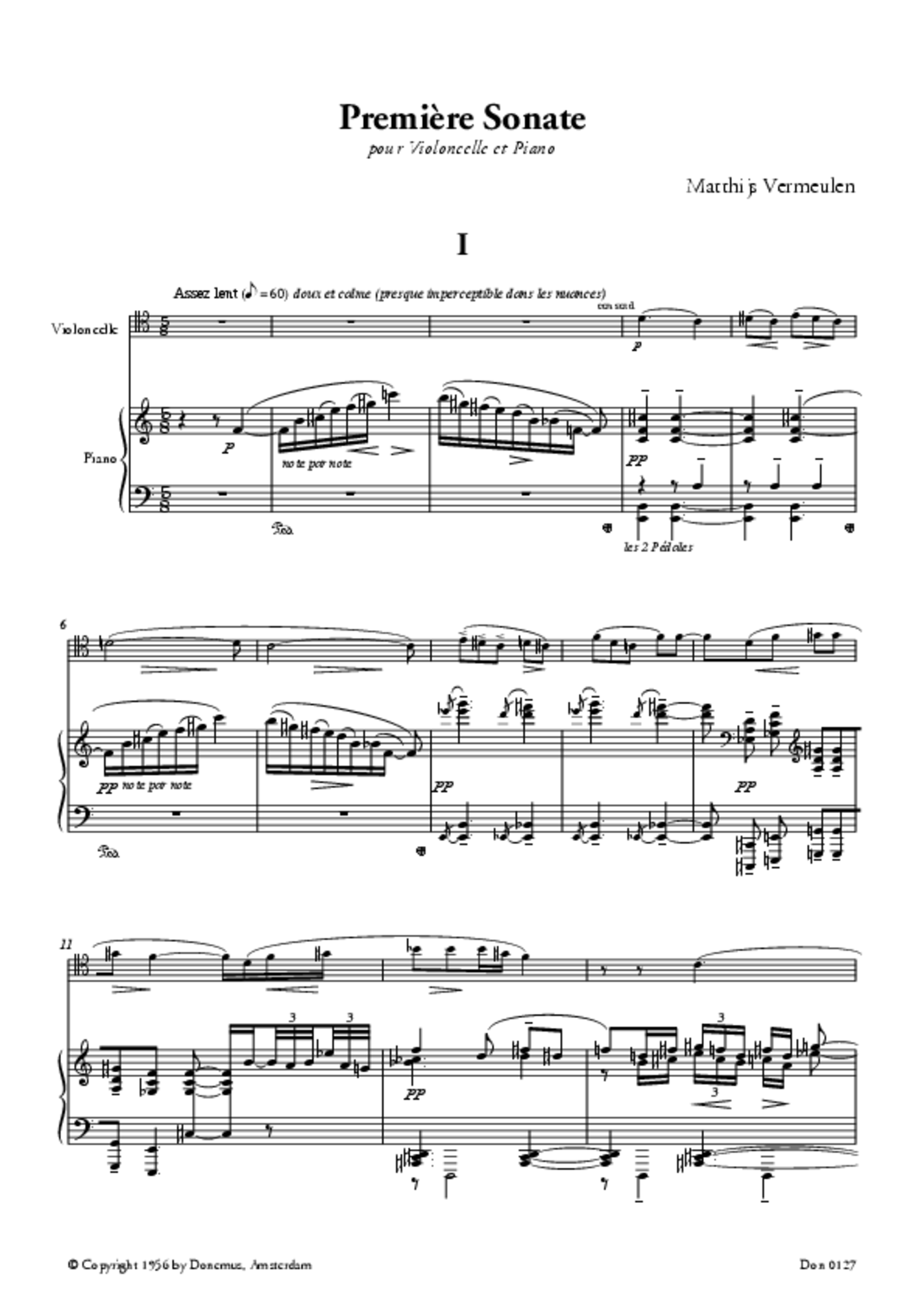

FIRST CELLO SONATA (1918)

A few days after Debussy's death on 25 March 1918 was announced, the French master was commemorated in Amsterdam with a concert of his Cello Sonata from 1915. The performance (by Thomas Canivez and Evert Cornelis) left a deep impression on Vermeulen, as seen from his review in De Telegraaf. The work – written for "such an old-fashioned combination as piano and cello" – opened up for him unexpected perspectives and possibilities. Shortly after this he started notating his own sonata.

That Vermeulen's composition is indebted to Debussy, can be seen from the melodic structure with its modality and chromaticism, and some bars of whole tone writing. Another characteristic feature which Vermeulen's sonata shares with Debussy is the alternation between lyric melodic parts and motoric passages, where the emphasis lies not in the exact realisation of the pitch but in the energetic movement (both composers give the cello vigorous pizzicati). Also derived from the Frenchman is the use of parallel intervals which serves to give a voice special colour. But in some cases Vermeulen goes considerably further than his model. Thus he departs from tonality already on the first page, where he creates a new sound idiom. Also Vermeulen's composition differentiates itself by polymelodicism (it is not rare for three independent melodies to sound simultaneously) and the level of wildness in the vigorous passages, which tends to be charming in Debussy but more volatile in Vermeulen (it is not without reason that the score is marked somewhere "très fougueux et farouche"). In order to reach this effect Vermeulen developed new pianistic techniques, such as in the opening bars of the second movement.

While composing his First Cello Sonata, Vermeulen was inspired by his love for his wife Anny, whom he had married that spring, and by the optimistic feelings which sprang from his steadfast faith that the Great War, which had taken millions of victims in its toll, would soon end. He associated the first movement – which, as if sensing its way from silence, starts with a rising and falling curve in the piano part, after which the cello enters with a chromatic, long outspun, tender melody – with Venus, and he characterised it later as "the awakening and then the resounding of a great love song in verses and contra verses". The second movement is mostly dynamic in character with often vigorous activity in the high and low registers of both instruments ("the turmoil followed by a great battle-song in the spirit of the victors"). This movement represents Mars. At the end the mood of the very beginning returns, as if – in Vermeulen's own words – "a canto d'amore could awaken again".

The vitality and joy of life which this work pronounce, and its organic form, make it a high point in the international literature for cello and piano.